Dire Financial Straits at UoE? NO!

First things first:

Please plan to join a UCUE branch information meeting open to all at 12:00 on Tuesday 3 December. Please check your e-mail for a link to join.

Read on for the REAL story!

In recent months, a narrative has taken hold: the University of Edinburgh is said to be in dire financial straits. This echoes wider troubles in UK higher education, but UoE management has not presented the data to show this is true. In fact, the publicly available financial reports do not corroborate their dire narrative about the University of Edinburgh. Below we present evidence that:

1. The University makes an operational surplus: in FY 2023, it earned on average £12.3m more than it spent every month.[i]

2. The evidence of financial troubles offered by the Principal is misleading; he wants to compel us to reach unrealistic surplus targets.

3. The University is wealthier than it has ever been: it has net assets of £2.7bn, up by £181m compared to 2022.[ii]

4. Staff costs are not ballooning: in fact, the evidence available from the most recent financial reports suggests they have been declining as a proportion of expenditures over the three past years.

5. A budget reflects priorities, and recent signs suggest UoE management’s priorities are out of step with the goals of a charity committed to teaching and research.

NB: Endnotes are not currently linked, please scroll to the end of the post to view the notes.

The University of Edinburgh generates a surplus from its operations every year

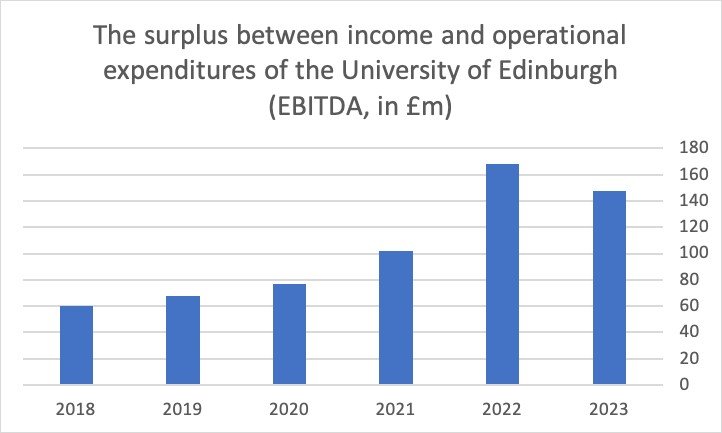

The University of Edinburgh generates a substantial operational surplus – its income is higher than its expenditures (as measured by the standard EBITDA formula). In FY 2023, the University’s income exceeded its operational expenditures by an average £12.3m per month, or £148m for the whole year.[iii] That year, income was 10.7% higher than expenditures, a very healthy ratio. This was one of the highest-ever operational surpluses for the University. In comparison, in 2019, pre-COVID-19, the University only made a £68m operational surplus and there were no talks of job cuts.

Over the history of the University of Edinburgh, only FY 2022 has been a better than FY 2023 in terms of EBITDA. This was thanks to the exceptional conditions created by the COVID-19 recovery. FY 2023 was the most recent in a streak of successful years from a financial standpoint, with the University making a cumulative £623 million in operational earnings between 2018 and 2023.

Talking about the level of expenditures without looking at how it is exceeded by income is misleading. In his November 2024 email, Peter Mathieson wrote that ‘the University costs £120m per month to run.’ This is a partial presentation of reality that ignores the fact that the University makes an operational surplus every year. FY 2024 is apparently no different from 2023 in this respect. As the Director of Finance told the University Court at their June 2024 meeting, “the University’s reported surplus [is] expected to be substantial”.[iv] Accounts for that year are not yet available to UoE Joint Unions or the public.

Takeaway: The University continues to make a surplus.

2. The evidence of financial decline is misleading

When Peter Mathieson talks about a “shortfall” in University finances, he is not referring to an actual deficit, but to the University not meeting its operational surplus targets. For instance, in the same Court meeting of June 2024, Senior Managers “forecast [a] shortfall against targeted EBITDA” (the standard measure of surplus). But this does not mean the University is making a loss. Nor does it mean the University administration is forecasting a loss. In fact, for the current FY, the University continues to forecast a surplus. If they missed the target, it means that the target was set at an excessively high level.

The management is moving the target to justify budget cuts and threats to jobs. At that same meeting of June 2024, Senior Managers decided to set an EBITDA target “at a higher level than previous proposals.” This is why Schools were suddenly told to cut their budgets at the start of this academic year, after already making plans: the management has decided that they need more surplus and that the place to take it from is student events, research funding, and tutors’ contracts (among others). Voluntary severance and compulsory redundancy (“if unavoidable”) are the next step in trying to meet this higher surplus aspiration.

Takeaway: Missing a target does not mean making a loss.

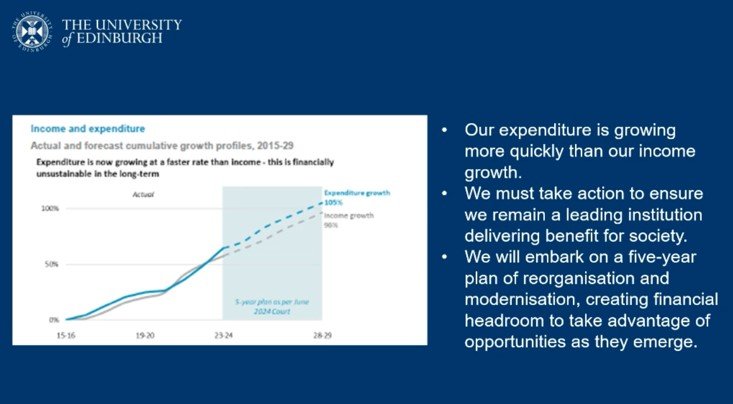

As a prime example of this strategy, let’s look at the chart presented by Peter Mathieson at the all staff meeting of 19 November 2024. It was the key evidence that the University needed to reduce staff costs, emphasizing what Mathieson explicitly described as a “deficit” in our finances. The graph is titled “expenditure is now growing at a faster rate than income”.

Let us count the ways this is a strange chart:

1. First of all, half of the chart is a speculative projection with none of the underlying assumptions or data provided.

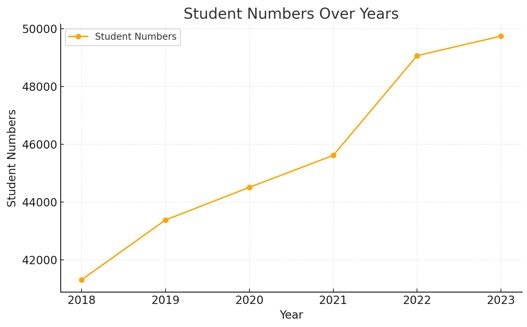

2. It suggests the University income (and expenditure) will nearly double by 2029, belying the recent messaging that the University will not “grow for growth’s sake” and that we are in a period of relative stasis with regard to student numbers.

3. It presents a difference in the rates of change of income and expenditures as if they were a difference in the real value. But just because the rate of change of expenditure is (projected!) to be higher than the rate of change of income does not mean expenditure is higher than income.[v] In the Principal’s presentation, differences in rate of change were routinely conflated with real differences in amount.

Through such misleading narratives, we believe that the Senior Management Team wants to take advantage of turmoil in other UK universities to justify job cuts here and compel us to reach unrealistic profitability targets. While this would give the University even larger margins for capital investments in vanity projects, this goes against the interest of staff and students.

Takeaway: A difference in the rate of change does not mean expenditure is greater than income. The University should be transparent about its financial data and modeling.

3. The University of Edinburgh is among the wealthiest in the UK

The University of Edinburgh has never been wealthier. At the end of July 2023, the University had £2.7bn (or £2,658m) in net assets. This means that its assets (approx. £3.5bn) exceed its debt and pension liabilities (respectively £536m and £352m) by £2.7bn.[vi] The net asset position of the University has been growing quickly over the past few years, thanks to the exceptional profitability of its operations and the income generated by the considerable assets it owns. Just between FY 2022 and FY 2023, the University’s net asset position increased by £181m. Between 2019 and 2023, the University’s net asset position increased by £604m, meaning that the University is now £604m wealthier than it was pre-COVID-19.

The University’s endowment is the third largest endowment in the UK. It is exceeded only by Oxford and Cambridge. At the end of July 2023, the endowment was worth £560m and it has grown since then. The endowment is complemented by considerable other investment assets including cash, public market stocks, bonds, and asset backed securities. These can be sold quickly to support the core mission of the University. Overall, by July 2024, the University’s total investment assets were almost a billion pounds (£956,276m).[vii] Moreover, the relatively small amount of debt that the University has contracted is composed of long-term loans that present no liquidity issue either.

Takeaway: The University has considerable financial resources at its disposal. This is about priorities.

4. University of Edinburgh staff costs are not a drain on its finances

The Principal has said that staff costs are 60% of University’s expenditures. This misrepresents the fact that over the past three financial years, staff costs have been falling when compared to overall expenditures. This is because staff salaries have grown at a lower rate than inflation, when other expenses were more in line with inflation. Our estimates, based on the University’s financial statements, show that the ratio between staff costs and overall expenditures was 59% in FY 2021. This ratio has fallen to 56% in FY 2022 and 55% in FY 2023.[viii]

We agree with the Principal that the increase in fees for the rest of UK students will have a relatively small impact on income. But he also says that UoE changes to the pay scale this year and increased National Insurance contributions squeeze the University untenably. We believe that this is an exaggeration. For instance, the cost of the pay scale revision was covered for the first three years through substantially reduced employer contributions to the USS pension scheme.

Despite the shortfall compared to the University’s recruitment targets, the University has grown its student body. Student numbers remain very high—requiring staff to teach and support them.

Takeaway: Staff are not a burden on the University—they are the core of its educational mission.

5. Where is the University spending money, then?

Focusing on staff as an unwanted expenditure – rather than the bread & butter of a teaching institution – leaves unasked: what else are we spending money on? In the coming days, we’ll dive into this more generally, but here’s a start.

One of the big and growing expenses is “capital” — a category that includes buildings. We summarise the reported expenditure below.

To be sure, there are necessary capital expenses: many of us know that there is insufficient space for lecturing, for instance. In addition, we need energy efficiency changes to meet UoE’s targets on reducing its emissions. But at the same time that staff are being told they are too expensive, spending on capital is moving ahead. At the June 2024 Court meeting, “significant capital spending” was approved despite “budgetary prudence” being advocated for teaching, learning, and research work.5 This is particularly worrisome because buildings cost not only a lot to build; they also cost a lot to maintain—in essence locking the University into the need to earn more money or save it by pruning elsewhere.

We can find other questionable expenses that do not require vilifying the staff who do the bulk of work at the University. For instance, in the past six years, the number of staff earning more than £100,000 a year has ballooned—indicative of a more general trend of inequality on campus.

In the coming weeks, we’ll report further on the financial status of the University, but in the meantime, don’t hesitate to be in touch with your local contacts and please raise these issues with your heads of subject and school.

Takeaway: If cost-cutting is the order of the day, a focus on staff ignores elephants in the room and will harm teaching and research.

If you want to know more, or ask any questions, please join us at 12:00 on 3 December for a hybrid meeting for all UCUE members. Check your e-mail for the link. If you are not a member of UCUE, or another campus union, now is the time to join!

UoE Joint Unions Finance Working Group

Endnotes

[i] See the University of Edinburgh Annual Report for the year ending July 2023, available here: https://uoe-finance.ed.ac.uk/accounts

Because the University’s financial year reflects the academic calendar, not the January – December calendar, when we refer to, say, the “2023 year” we mean the 12 months ending in July 2023.

[ii] See 2022-2023 Financial Statements, p. 49.

[iii] This operational surplus is measured by the EBITDA (Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation, and Amortization) indicator, which is now the standard indicator to measure the operational profitability of businesses globally and has been chosen by the University Court to measure the performance of the University’s operations. This indicator can be found in the 2023-2023 Financial Statements of the University, p. 3.

[iv] In part this reflects beneficial movements in the USS provisions, but the positive operational surplus is a long-standing trend. For the Director of Finance’s comments, see Item 5: https://www.docs.sasg.ed.ac.uk/GaSP/Governance/Court/2023-2024/20240617-Court-Minute-Web.pdf

[v] If one car is going steady at 40km/hr but another car begins accelerating from 20km/hr, it will take a while before the slow car’s acceleration means its speed passes the fast car.

[vi] See 2022-2023 Financial Statements, p. 113.

[vii] See https://uoe-finance.ed.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2024-10/Investments.pdf

[viii] In our calculation, we exclude exceptional USS provision changes from both expenditures and staff costs; if we were to include them, they would have fallen from 60% in 2021 to 57% in 2023.